Time is the most undefinable yet paradoxical of things; the past is gone, the future is not come, and the present becomes the past even while we attempt to define it.

Charles Caleb Colton

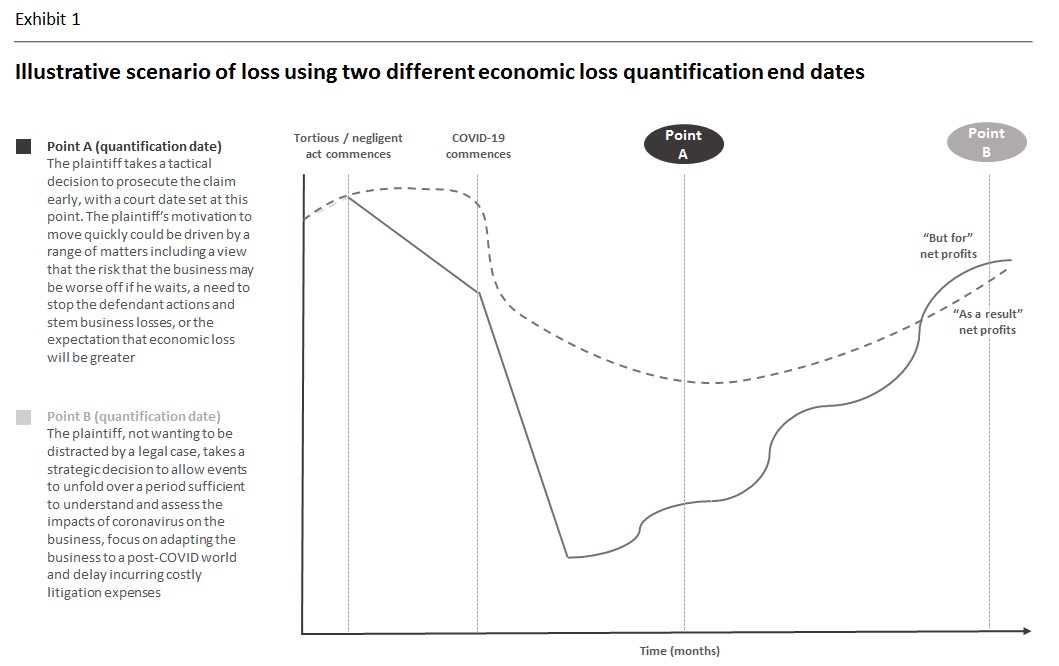

With timing being the subject of the first article in our COVID-19 economic loss quantification series, it seems fitting that it is the issue that wraps up the series. I first discussed timing in the context of assisting clients attribute losses between a primary event (such as some tortious or negligent act) and the intervening event, in this case, COVID-19. In this article, I reflect on the risks and evidentiary challenges associated with determining the date on which the economic losses cease.

The uncertainties in an economic loss claim affected by an intervening event are, on balance, more likely to decrease as the period of time passes. This is simply because the passing of time allows us to understand how the business actually adapted to the intervening event and reliable information critical to the loss calculation becomes available. Let me explain by using the following example:

- The defendant’s actions impaired the plaintiff’s ability to respond to COVID-19 (the intervening event), resulting in greater losses than would have been incurred, but for the defendant’s actions. On that basis, the period of loss suffered by the plaintiff as a result of the defendant’s actions is assumed to extend into the post-COVID-19 period;

- Using scenario analysis (as discussed in last week’s article), the plaintiff was able to reasonably forecast the business’s net profits, but for the intervening event; and

- The combined impact of the defendant’s actions and COVID-19 caused the plaintiff to take mitigating actions, including scaling back operations, implementing cash flow optimisation strategies and using the time to execute changes to the business’s operating model. Consequently, the business emerged from the COVID-19 health crisis a leaner, more efficient and profitable competitor; and

To demonstrate the significance of end dates in economic loss calculations where the economic loss has been exacerbated by an intervening event, we’ll also assume that the plaintiff’s choices of economic loss end date are at Point A and Point B, as set out in Exhibit 1.

For the reasons such as those outlined in Exhibit 1, the plaintiff took the tactical decision to use Point A as the end date of the economic loss calculation. That decision may have, for example, been based on the results of the scenario analysis that used information available at that time, which suggested that losses were maximised at that date. In doing so, the plaintiff has made certain assumptions about the path of the coronavirus, and taken a view about the easing of restrictions and ensuing economic recovery.

At Point A, we’re very much in the middle of the health crisis; State governments are moving at their own pace and declarations about restrictions are constantly changing. It’s fair to say that at Point A, there likely exists a high degree of business ambiguity and uncertainty. While that ambiguity and uncertainty could be partly mitigated through appropriate scenario analysis, it is unlikely to be avoided.

It is therefore likely (and reasonable) for the Court to apply a rate of vicissitudes that appropriately matches its assessment of the ambiguity and uncertainty inherent in the “but for” calculation of net profits. Presenting the Court with the results of the scenario analysis, including how and what risks were incorporated, may assist in focussing the Court’s conclusions on unmanaged risks and achieve a more favourable and commercial view on vicissitudes.

In contrast, a plaintiff may choose to take a more strategic approach by selecting Point B as the economic loss calculation end date. The additional passing of time would (hopefully) provide greater certainty, say, on the easing of restrictions and enable a better understanding of how COVID-19 may have changed economic fundamentals. Quantifying losses with a greater degree of certainty would assist the Court applying a commensurately lower rate of vicissitudes.

From an evidentiary perspective, opting for Point B over Point A has some advantage. Since COVID-19 emerged as a threat to the global economy, there has been a diverse and constantly evolving speculation on the economy re-rebound: first came the V-shaped recovery, followed by a U-shaped recovery, and more recently, predictions of an L-shaped recovery. Forecasting relies on having reliable, credible and robust information available and it’s fair to suggest that much of the information released during the earlier stages of the pandemic did not satisfy that criteria. That is not to say that the information available at that time was so unreliable that Point A is not a viable option; rather, it’s important to recognise that significantly greater risk accompanies that choice because of the velocity at which “current” information and predictions become redundant and are being continuously revised and replaced as new information becomes available.

So that wraps up BRI Ferrier’s COVID-19 economic loss quantification series. I hope you’ve enjoyed reading the articles and that they have provided you with an alternative framework for assessing economic loss. I’m more than happy to have a chat about any questions you have on the content covered or how it can be applied to your current matters.

Need advice?

Early forensic accounting input may assist in developing the best legal strategy. We may be able to give a broad overview of the main issues after a brief review of available financials and an outline of the background to the matter. We aim to help, so please feel free to contact:

Paul Croft Jacqueline Woods

pcroft@brifnsw.com.au jwoods@brifnsw.com.au

+61 418 411299 +61 417 472668