Since the Federal Court’s decision in Apand Pty Limited & Ors v Kettle Chip Co Pty Limited[1] 20 years ago, the world has become a more complex place. Automation, AI and the volume of data and interconnectedness created through advances in technology are among a myriad of factors that have fundamentally re-shaped the ways organisations operate.

To see how well the decision in Apand stacks up in light of today’s dynamic environment, I adopted a very non-traditional approach: systems thinking.

What is systems thinking?

Systems thinking emerged in the early 1990s and today is used by businesses in scenario planning and developing solutions to complex problems. Systems thinking recognises that every decision we make has consequences: viewing our environment as a system of constituent parts helps us anticipate and plan for the consequences of our decisions on other parts of the system. Put another way, it is a disciplined way of understanding dynamic relationships to make better choices and avoid unintended consequences. In doing so, it removes the focus on the immediate consequences of our actions.

For example, consider a new freeway: initially, it reduces congestion, but as potential freeway users notice the lack of congestion, their usage of the freeway increases, creating more traffic and leading to increased congestion on the freeway.

A core concept of systems thinking is feedback, which comprises all the factors that influence behaviour including: policies and decision-making processes, information channels, rewards systems, expectations, time lags and culture. Together, those elements form the underlying structure of a system, which drives behaviours that in turn, lead to the events we observe.

Applying systems thinking to Apand (as an organisation)

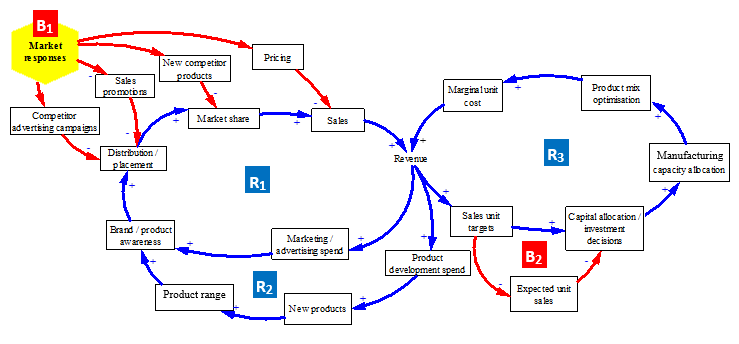

Causal loop diagrams (CLD) help us visualise the critical feedbacks that regulate the forces of our systems.

I’ve created a simplistic model to illustrate how events may have evolved as a result of Apand’s decision to infringe a competitor’s product. While hypothetical, the CLD presents a holistic view of the temporal benefits generated by Apand, which exceed the account of profits awarded by the Federal Court.

The model comprises five loops: three reinforcing (blue) loops (labelled R1, R2 and R3) and two balancing (red) loops (labelled B1 and B2).

Loops R1 and R2 illustrate how success breeds success. The increase in sales achieved from selling the infringing product generated more revenue to spend on marketing and placement activities, increasing Apand’s marketing share, sales and therefore, revenue (R1). Increased revenue also creates additional funding available for product development, expanding Apand’s product range and driving increases in market share, sales and revenue (R2).

Loops R3 and B1 relate to Apand’s internal capital / resource allocation. Operating at capacity, Apand would have needed to reallocate capital / resources across its manufacturing division to create the capacity to manufacture the infringing product, leading to an adjustment in its product-mix strategy to optimise its production costs. As long as sales continue to meet or exceed targets, Apand’s management would have remained incentivised to maintain its newly optimised product-mix strategy (R3). However, the action taken by Kettle Chip would have caused Apand to adapt its capital / resource allocation strategy, leading to lower sales and revenue (B2).

Time lags are a typical feature of a system. In this case, there is a time lag between Apand undertaking the infringing activities to win market share, and the market responses by competitors to recover lost market share and sales (B1).

Figure 1: hypothetical CLD

4 reasons for adopting systems thinking when quantifying an account of profits

- Equity may not otherwise be achieved. The existing remedy allows the infringing party to retain any profits indirectly earned as a result of its infringing activities. If a share of the entire profits are not passed on to the wronged party, the infringing party avoids having to “account for the actual profit, no more and no less”[2].

- It is feasible to reasonably quantify the value of total profits. The causal loop diagram highlights a range of critical data points (market share, brand awareness, capital decision benchmarks, product/mix outcomes) organisations typically collect, use and monitor to assist them in assessing the outcomes of their decisions.

- Systems thinking has already been applied in written judgments. The trial judge, Burchett J, applied systems thinking in his judgment by opining on the potential consequences of competing with an unsuccessful product: low market impact (and by inference, sales) and the potential cannibalisation of one’s own market share (at APIC 37,426; ALR 137)

- The decision in Apand to allocate a share of the capital profits implicitly adopts a system perspective. The valuations placed on intangible assets and goodwill would have reflected management’s expectations as to the future profits, which includes the system consequences associated with Apand’s decision to manufacture and sell the infringing product,